The Sinking of HMAS Armidale

Full credit to the Royal Australian Navy for the below images and retelling.

“An important yet neglected episode in Australia’s wartime history, the tragic story of the Armidale combines themes of bravery, sacrifice, and endurance. A hundred lives were lost when the ship went down, but in an extraordinary feat of survival, and despite continuing attacks from bombers and sharks, 49 men managed to survive at sea for up to eight days before being rescued.”

– The Australian War Memorial

The Australian Minesweepers (Corvettes)

HMAS Armidale was one of sixty Australian Minesweepers (commonly known as corvettes) built during World War II in Australian shipyards as part of the Commonwealth Government’s wartime shipbuilding programme. Twenty were built on Admiralty order but manned and commissioned by the Royal Australian Navy. Thirty six (including Armidale) were built for the Royal Australian Navy and four for the Royal Indian Navy.

These ships established an enviable reputation in the RAN as ‘maids of all work’ but were also renowned for ‘rolling on wet grass’ by those who served in them.

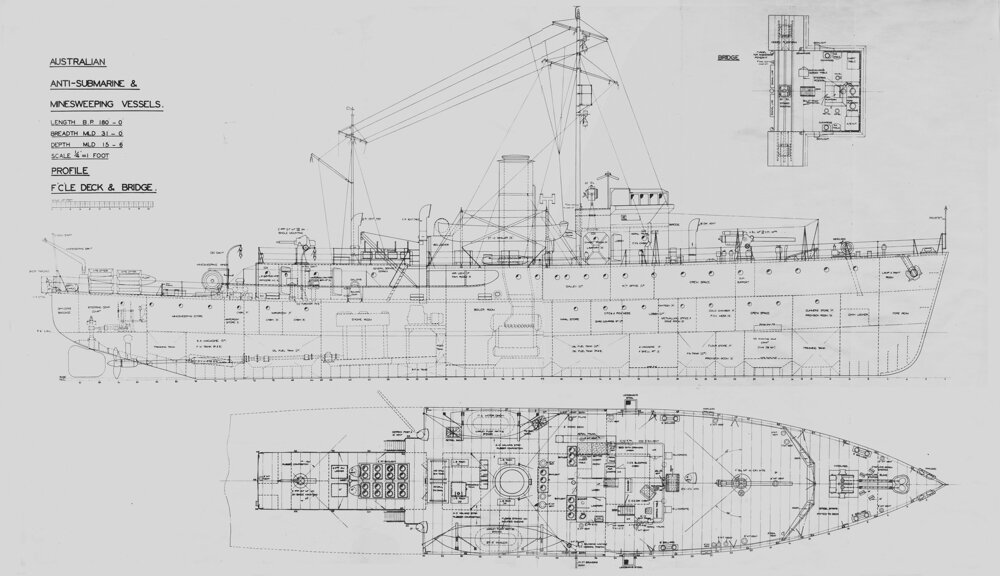

The general arrangement plan of a Bathurst Class Corvette – Sourced from the Royal Australian Navy

Following a workup period Armidale was brought into operational service as an escort vessel protecting convoys operating between Australia and New Guinea. That service ended in October 1942 when she was ordered to join the 24th Minesweeping Flotilla at Darwin. Armidale arrived at Darwin on 7 November 1942.

On 24 November 1942 Allied Land Forces Headquarters approved the relief/reinforcement of the Australian 2/2nd Independent Company which at that time was holding out in Japanese occupied Timor.

The withdrawal of 150 Portuguese civilians was also approved and consequently plans were made in Darwin for HMA Ships Castlemaine (Lieutenant Commander Philip J Sullivan, RANR(S)), Armidale and Kuru (Lieutenant JA Grant, RANR), a shallow draught, 76 foot wooden motor vessel, to effect the relief operation which was code-named Operation HAMBURGER.

The proposal was for the three ships to each make two separate runs into Betano on Timor’s southern coastline. The first run was planned for the night of 30 November-1 December. HMAS Kuru sailed from Darwin at 22:30 on 28 November preceding the two corvettes. She was delayed en route due to adverse weather conditions and consequently did not reach Betano until 23:45 on 30 November.

Meanwhile Armidale, in company with Castlemaine, had left Darwin at 00:42 on 29 November. In Armidale were 61 Netherlands East Indies troops, two Dutch officers and three members of the 2nd AIF. At 09:15 on the morning of 30 November when, 120 miles from their destination, the two corvettes came under aerial attack from a single enemy aircraft. Although neither ship sustained any damage or casualties, concerns were raised that the mission may have been compromised. The attack was duly reported and orders were received to ‘press on’, with an assurance that RAAF Beaufighter aircraft had departed to provide cover. The ships were subjected to two more air attacks, each by formations of five bombers which dropped no less than 45 bombs and machine gunned the ships from a low level. According to Armidale, the promised Beaufighters arrived in time to drive off the bombers and both ships escaped serious damage or injury, reaching Betano at 03:30 on 1 December. Disappointingly there was no sign of Kuru and a decision was made to return to sea and make as much ground to the south as possible before daylight.

Meanwhile, Kuru, with no knowledge of the attacks affecting the arrival of the corvettes, embarked 77 Portuguese before sailing without delay. At dawn Kuru was sighted by Castlemaine 70 miles south of Betano and she subsequently closed to conduct the transfer of her passengers to the corvette. Following the rendezvous Kuru received orders from Darwin to return to Betano and complete the mission that night. No sooner was the personnel transfer complete when enemy bombers again appeared necessitating Kuru to run for cover in a nearby rain squall.

As the senior officer, Castlemaine’s captain quickly appraised the situation. Kuru had orders to return to Betano, Armidale had troops on board to be landed there, and, to further complicate matters, a signal had been received to search for two downed airmen from a Beaufighter some 150 miles to the south east. Sullivan’s preference was to exchange passengers with Armidale so Castlemaine might escort Kuru back to Timor, however, the presence of enemy aircraft ruled that out. Consequently Armidale and Kuru were ordered to return to Betano to complete the troop reinforcement operation while Castlemaine went in search of the downed airmen en route back to Darwin.

As Kuru and Armidale steamed northwards they both came under fierce aerial attack becoming separated in the process. For almost seven hours Kuru dodged bombs suffering minor damage to her engine and losing her assault boat that was under tow. Grant reported the damage to Darwin but was told that the operation was to be carried through. This instruction was later rescinded when the presence of Japanese cruisers approaching the area was reported. Kuru then shaped a course for Darwin.

At approximately 13:00 on 1 December five Japanese bombers were spotted by Armidale’s lookouts. Without adequate air cover there was little hope of surviving the attack and a signal was sent to Darwin requesting urgent fighter cover. For the next half an hour Armidale’s gunners beat of successive Japanese attacks and the ship escaped serious damage. In the mean time a signal was received from Darwin advising that the much needed fighters would arrive at 13:45.

Shortly before 15:00 Armidale was attacked by nine bombers, three fighters and a float plane. The fighters split up and came in at low level straffing Armidale’s decks with machine gun fire. With her gunners thus distracted, the torpedo bombers mounted their attacks from different directions as Richards manoeuvred desperately to avoid their torpedoes. In spite of the brave resistance, the ship was hit twice by torpedoes, immediately heeling over to port. At that point Richards gave the order to abandon ship. Rafts were cut loose and a motor boat freed from its falls before men took to the water. Their ordeal, however, was far from over. The Japanese airmen then pressed home further attacks machine gunning the survivors.

Leading Seaman Leigh Bool who survived the ordeal later recalled:

“Two or three [aircraft] went right across the ship and they apparently were using their torpedoes as bombs. These did no damage although several of the torpedoes hurtled low right across the ship. However, the others hit us within two or three minutes of the commencement of the attack. We were hit on the port side forward, causing the ship to heel over at an angle of 45 degrees.

The Armidale was going fast and the captain ordered us to abandon ship. Ratings were trying to get out lifesaving appliances as Jap planes roared just above us, blazing away with cannon and machine guns. Seven or eight of us were on the quarterdeck when we saw another bomber coming from the starboard quarter. It hit us with another torpedo an we were thrown in a heap among the depth charges and racks.

We could feel the Armidale going beneath us, so we dived over the side and swam about 50 yards astern as fast as we could. Then we stopped swimming and looked back at our old ship. She was sliding under, the stern high in the air, the propellers still turning.

Before we lost her, we had brought down two enemy bombers for certain, and probably a third. The hero of the battle was a young ordinary seaman, Edward Sheean, not long at sea, who refused to leave the ship.

Sheean had no chance of escape. Strapped to his anti-aircraft gun, he blazed away till the last. One of the Jap bombers, hit by his gun, staggered away trailing smoke, just skimming the surface until it crashed with a mighty splash about a quarter mile away.”

Wireman William Lamshed was another who survived the sinking recalling Armidale’s last moments both from his action station in a small workshop on the corvette’s port side and from in the water:

“The workshop was about 1 metre in width and 2 metres in length with a phone to the bridge. My duties were to receive instructions for setting of the depth charge detonators, when hunting down subs. This was my station regardless of what action was in progress.

When we first saw these different looking planes coming, we just knew we were in big trouble, and that our end might be near, so I quickly went to my hideyhole, as I called it, and cringed in a corner, waiting to be blown to pieces. I was wearing shorts beneath my boiler suit, had only slippers on my feet, a tin hat on my head and my deflated Mae West [life preserver]. My only other possession was a Joseph Rodgers ‘Bunny’ pocket knife, which I acquired when rabbit trapping and hunting as a young lad in my Victorian rural home town. A torpedo hit us on the port side amidships and this caused my steel workshop door to burst open. I knew then the ship was doomed and so I attempted to leave through the doorway, only to be met with a huge wall of water from the explosion. This somehow sent me over the stern of the ship and into the swirling wash from the propellers. I had no control over my movements at that time, for everything happened so swiftly, but I was aware that I had lost my tin hat and my slippers. Later when I had time to think, I realised how lucky I had been, for I could have been killed then by being bashed into the davits that criss-crossed the stern of the ship.

As the ship sped away from me the port propeller was still under water and the starboard propeller was lifting out but still turning. The water around me then became calm, but the same couldn’t be said for me. I suddenly realised I was being left behind and nobody knew I was overboard. The Zeroes were raking the ship with cannon and machine gun fire from their noses and wings, then another torpedo struck on the starboard side and the ship split in two. Then another torpedo was dropped like a bomb, but it overshot the ship, hit the water and disappeared.

I was now in complete panic as my ship was sinking in front of my eyes, with all still on board trying to escape. Now the front of the ship was turning on its side and going down. The rear section was leaning on an angle, when the after Oerlikon gun started firing and I saw tracers actually hitting a dive bombing Zero which flew over my head and disappeared into the sea about a quarter of a mile away. A brilliant bit of shooting, I thought, considering the deck was at such a steep angle and that the gun was still firing as the ship sank under the water.”

Ordinary Seaman Edward Sheean

Ordinary Seaman Edward “Teddy” Sheean, an 18 year old rating from Latrobe, Tasmania, was one of those injured during the attacks. In spite of injuries to his chest and back he helped to free one of the ship’s life rafts, before scrambling back to his post on an Oerlikon gun, mounted behind the bridge. Strapping himself to his weapon he opened fire shooting down one bomber and keeping other aircraft away from his comrades in the water. He was seen still firing his gun as Armidale slipped below the waves just after 15:10 in position 10°S, 126°30´E. Sheean was posthumously awarded a mention in dispatches for his bravery and one of the Australian-built Collins Class Submarines, HMAS Sheean, is named in his honour.

The Survivors

When the marauding Japanese departed, the survivors found themselves in the water with two boats (a motor boat and a whaler) a Carley float and a raft that had been successfully freed from the sinking corvette. The men remained together until the afternoon of 2 December when Lieutenant Commander Richards made the difficult decision to set out for help in the motor boat which at that time carried 16 of his ship’s company and some Dutch service personnel. The motor boat had sufficient fuel for about 100 miles but from the outset the motor proved unreliable forcing those on board to row for the first 28 hours. The motor was eventually encouraged to start and the vessel was later sighted by a reconnaissance aircraft from Darwin on Saturday 5 December. By then the boat was approximately 150 miles WNW of Darwin and roughly 150 ESE of where Armidale had sunk. The sighting of the motor boat was the first confirmation to naval authorities in Darwin that Armidale had been lost.

By that time, having himself observed no sign of searching aircraft, Lieutenant LG Palmer, RANR, in command of Armidale’s 27 foot whaler, was also underway in search of help. Embarked in that vessel were 25 of Armidale’s crew and three soldiers of the 2nd AIF. Remaining drifting on the raft were 28 of the ship’s company while on the Carley float were 21 Dutch troops. Their future was dependent on Richards or Palmer being spotted.

HMAS Kalgoorlie left Darwin at 11:40 on 5 December reaching the vicinity of the sighting of Armidale’s motor boat at 02:30 the next morning. There she proceeded to search for the survivors coming under aerial attack herself from two Japanese bombers. The attack saw 16 bombs dropped by the aircraft but the corvette fought back receiving no damage. At 22:00 that evening a red flare was sighted and an hour later she rescued 20 men from the motor boat under the command of Richards. Two of its number had died during the voyage – Ordinary Seaman Frederick Smith and one of the Dutch soldiers. The others were in poor shape and in light of this Kalgoorlie’s commanding officer made the painful decision to cease searching and repatriate them to Darwin which he reached at 13:30 on 7 December. Among the survivors was Able Seaman Eric Millhouse who had previously survived the loss of HMAS Canberra in August 1942.

On 7 December, the raft was sighted by searching aircraft and on the following day both the whaler and raft were again observed. HMAS Kalgoorlie subsequently located and rescued the occupants of the whaler, however, the rafts and their occupants were never seen again.

A Catalina flying boat was despatched from Cairns to pick up these survivors and reached the area on the afternoon of 8 December 1942. One of the Catalina aircrew took this picture, but the aircraft was unable to land because of the rough sea state. Despite exhaustive air and sea searches and the rescuing of other survivors, these pictured survivors were never seen again after the Catalina departed from the area.

“We rowed all night, towing the raft with a crowd of men on it, we wanted to put as great a distance as possible between the raft and enemy. Soon after dawn we divided our provisions. What we took was not great, just two small tins of bully beef, six tins of unsweetened milk and a beer bottle of water. As there were 29 of us in the whaler and as we had hard work ahead, it was indeed a meagre larder.”

– Leading Seaman Leigh Bool

Out of a total of 83 naval personnel, comprising five officers and 78 ratings, 40 (two officers and 38 ratings) lost their lives. Losses of Netherlands East Indies personnel were two officers and 58 soldiers.